Growing Kingsley

The Homestead Boom

The story of Kingsley begins with a rush of hope. In the 1910s, the eastern Montana plains saw a surge of newcomers drawn by promises of land and self‑reliance. Powder River Country—prairies, breaks, and creek bottoms like the Mizpah—offered space enough to imagine a future. Word traveled by letters, newspapers, and railroad posters: “rich lands still untouched.”

Families arrived by rail to hubs like Miles City and then by wagon, horseback, or by foot to stake a claim. The Kingsley settlement, eight miles north of Broadus, grew from scattered log cabins and dugouts into a tight‑knit community. It was just one of thousands of homestead settlements across the West – names like Sayle, Sonnette, and Stacey.

Immigrants and second‑generation Americans from Eastern and Midwest coal towns and farm villages believed a modest acreage could support a family if they worked hard enough. Many did—at least for a while. But success on the northern plains required more than grit. It demanded timing, neighbors, and weather on your side. Those elements—and the laws that first opened the door—shaped the fate of Kingsley and of Powder River Country as a whole.

Laws that Opened the Plains:

The Expanded Homestead Acts

Montana’s early‑20th‑century homestead boom was sparked by a series of federal laws that dramatically changed who could claim land—and how much. Alongside homestead entries, many settlers also filed “desert claims” under the 1877 Desert Land Act to secure irrigable bottoms and water sites, expanding workable acreage when paired with a homestead or stock‑raising entry.

-

The original Homestead Act (1862) promised up to 160 acres to those who lived on and improved their claim.

-

The Desert Land Act (1877) created “desert claims” on arid lands—typically up to 320–640 acres, depending on state—available at low cost if the claimant developed irrigation within a set period (commonly three years). Families in Powder River Country often paired a desert claim with a homestead to assemble enough water and hay ground for a viable operation.

-

The Enlarged Homestead Act (1909) recognized the challenges of arid country and increased certain claims to 320 acres, with cultivation requirements intended to bring more land under the plow.

-

The 1912 amendments shortened residency to three years, making it easier to “prove up.”

-

The Stock‑Raising Homestead Act (1916) opened designated grazing lands at 640 acres—less for farming than for raising cattle and sheep, with requirements to make improvements and develop water.

These changes rippled through eastern Montana. Land offices filled; surveyors fanned out to plat sections and townships; and communities like Kingsley took root. More acres on paper, however, did not guarantee a living in a landscape where moisture is precious, soils vary, and seasons can turn on a dime. The same policy that invited thousands also set the stage for hard choices when drought and winter hit.

1910 marked the end of the old West and the beginning of a new “barbed wired fences and grass turned wrong side up.”

— Mac McCurdy

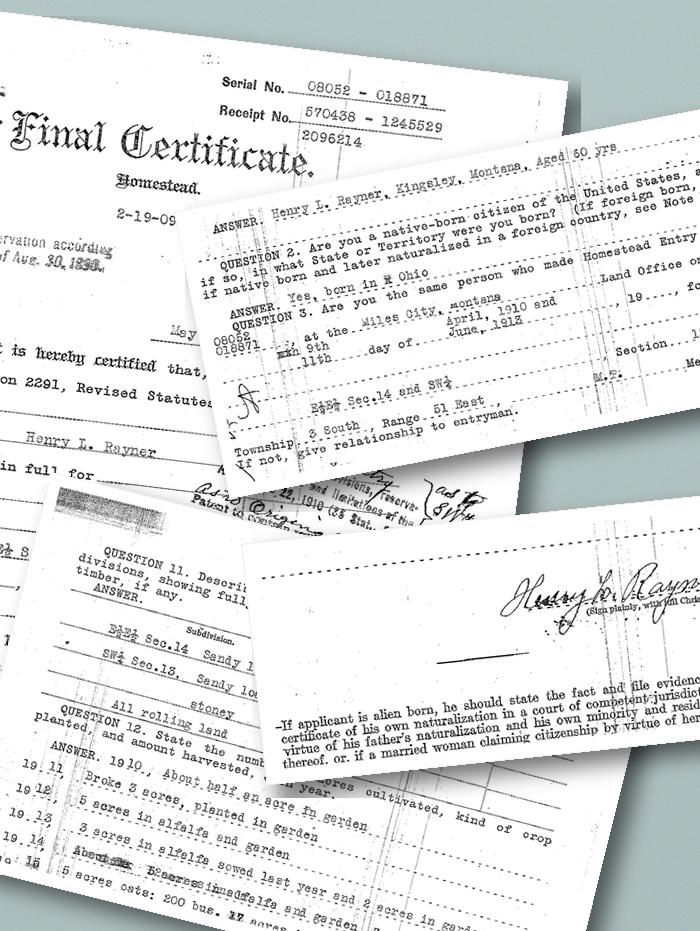

Proving Up on Your Claim

To ‘prove up’ was to turn a claim into a deed. After filing at the land office, a homesteader marked the corners and moved in, throwing up a sod or log house, fencing a corral, digging a well where possible, and breaking ground for grain and a garden. Years of residence and cultivation followed, measured by acres plowed and seasons endured. Neighbors mattered; two would swear that the work was done. Fees were paid, papers signed, and the patent arrived—title in hand at last. In Kingsley, luck and moisture set pace: wet years led to expansion; dry cycles forced sales.